2021 Apartment Housing Outlook

Paula Munger

The year 2020 was unlike any other in modern history, marked not only by a global health crisis but social unrest, a contentious Presidential election and a recession that drew comparisons to the Great Depression. As the year came to a close, optimism about impending vaccine distribution and clarity over the election was outweighed by dire warnings from public health officials about expectations for rising infections and deaths through the winter months.

The final jobs report of 2020 was a glaring reminder that the economic recovery may remain on shaky ground for months to come. Only 245,000 jobs were added in November, bringing the total jobs recovered to 12.3 million out of 22.2 million lost earlier in the year. Increased infection rates have typically led to business closures and/or capacity reductions, meaning the labor market will continue to struggle until the virus is firmly under control. While vaccines will go a long way toward economic recovery, lack of public confidence in their safety may undermine their impacts.

The final jobs report of 2020 was a glaring reminder that the economic recovery may remain on shaky ground for months to come. Only 245,000 jobs were added in November, bringing the total jobs recovered to 12.3 million out of 22.2 million lost earlier in the year. Increased infection rates have typically led to business closures and/or capacity reductions, meaning the labor market will continue to struggle until the virus is firmly under control. While vaccines will go a long way toward economic recovery, lack of public confidence in their safety may undermine their impacts.

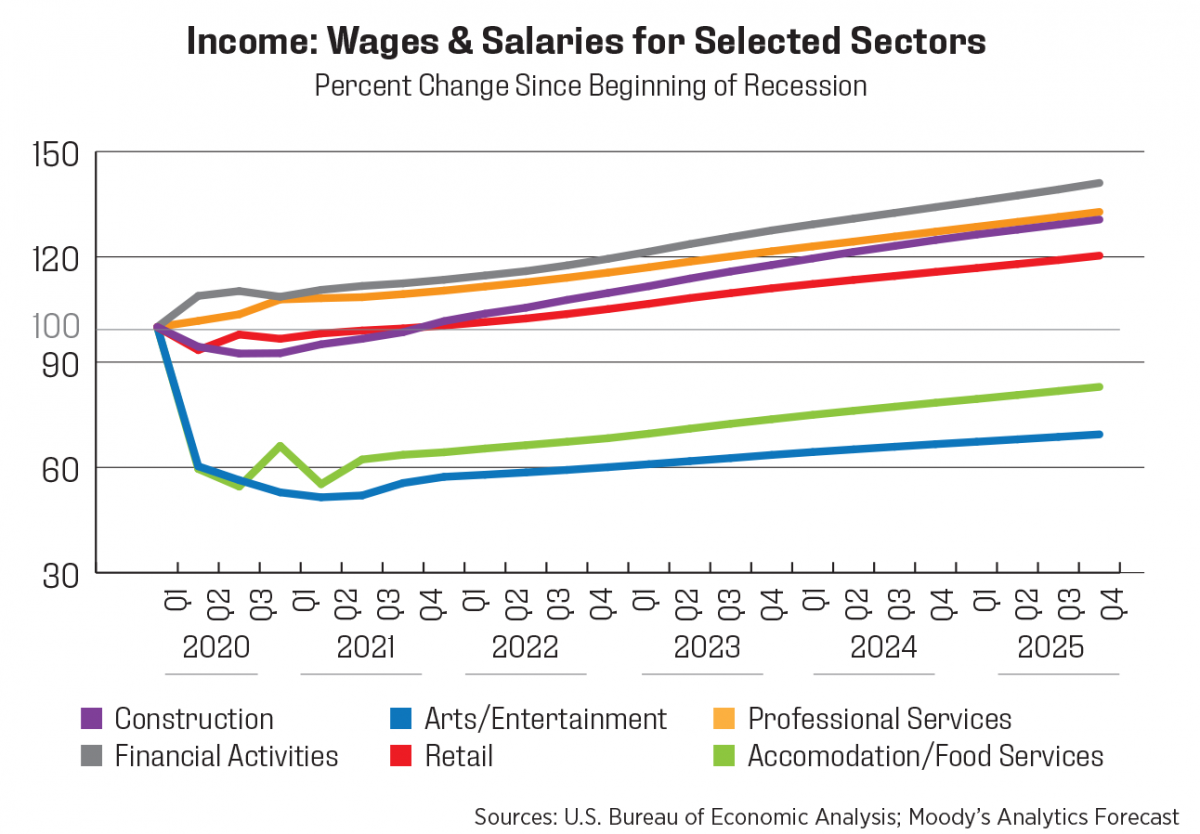

Although forecasts for the timing and duration of the recovery vary, one thing on which all economists agree is the absolute necessity for another round of fiscal stimulus. The CARES Act kept businesses running and consumers afloat and its impacts were crystal clear across many economic indicators. The V-shaped recovery has thus far been elusive, save for the for-sale housing market. The most likely outcome at this point appears to be K-shaped, translating into bifurcated conditions where lower-paying jobs and wages remain depressed and higher-paying jobs, with the ability to work remotely, thrive.

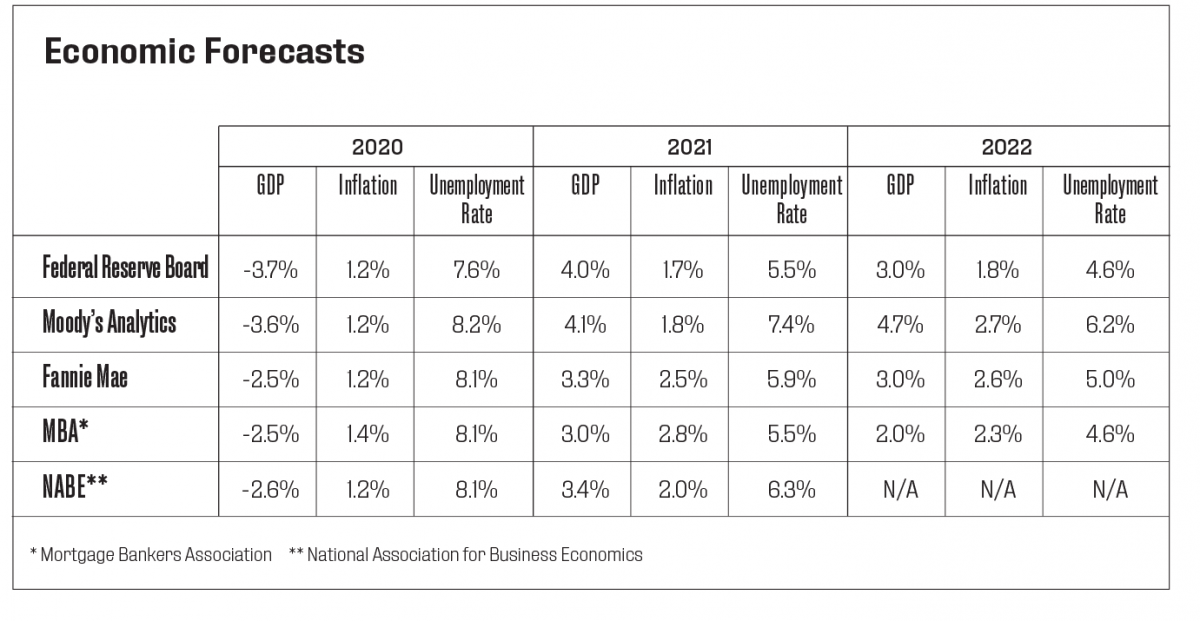

GDP forecasts for 2021 range from 3.0 to 4.1%, with expectations for it to return to 2019 levels by the end of 2021. The labor market, however, will take longer to recover with none of the forecasts included in this analysis expecting the unemployment rate to return to 2019 levels for at least the next two years. Some forecasters do not expect to see employment levels restored until the end of 2024, partially driven by permanent job losses on the order of 5-10%.

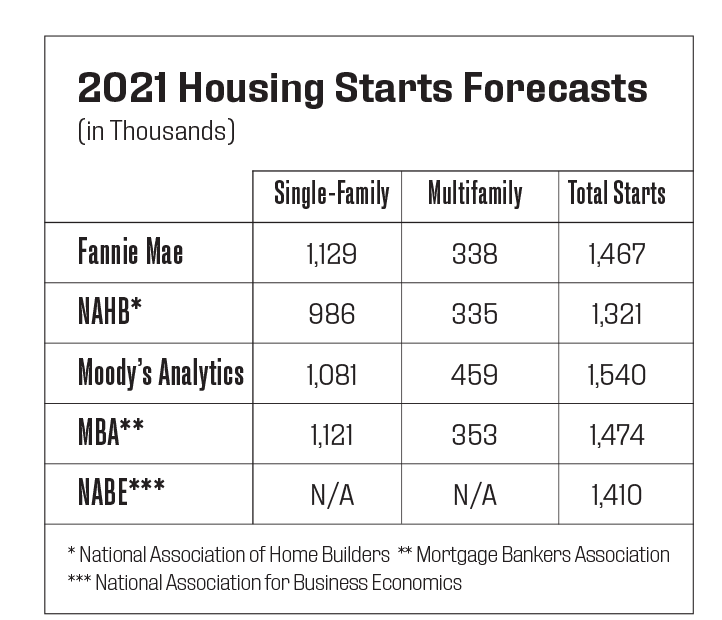

The single-family housing market hit records across many indicators in 2020, so it should not come as a surprise that forecasts are calling for levels of starts not seen since 2006/2007. Forecasts for multifamily starts show a wider dispersion, but on average, are only slightly off levels seen in recent years. But topping 500,000 annual starts, which occurred at the end of 2019 and into 2020, seems highly unlikely in the near-term as permitting activity shows signs of moderating amid robust levels of completions.

The economic bifurcation of the economy bled into the apartment market as owners of smaller, older and Class C properties saw delinquencies rise while institutional owners generally had better outcomes. Similarly, but with some exceptions, properties in large urban cores experienced decreased rents and occupancy levels while suburban properties and those in smaller, more affordable cities performed well.

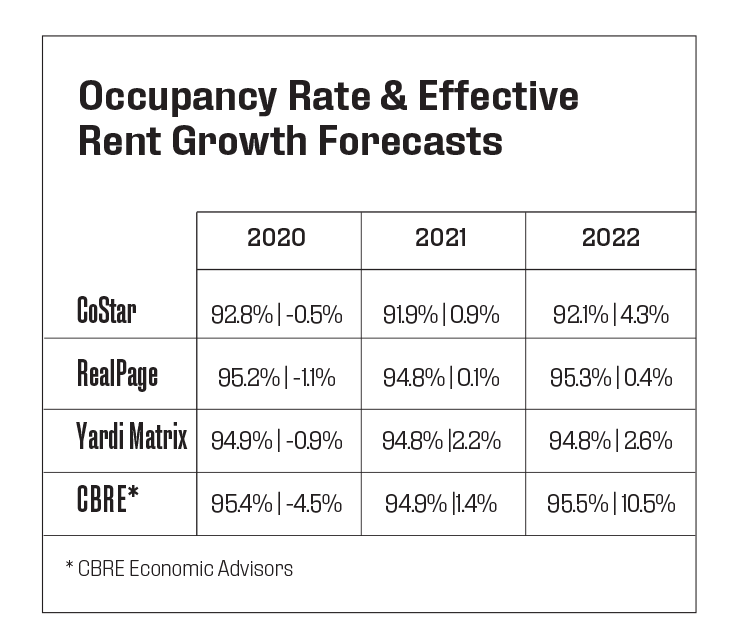

Forecasts for apartment fundamentals for predominantly institutional-grade properties indicate a bottoming of the market in late 2020 and into 2021. On an annual basis, rent growth is positive albeit muted while occupancy rates post slight declines before ticking up in 2022. New supply forecasts range from 300,000 – 400,000 units in 2021 as construction delays because of the pandemic and downturn cause timelines to get pushed into next year. Apartment owners and operators are preparing for a challenging 2021, budgeting for declining revenues and increasing costs, both on the operating side and for capital expenditures.

Forecasts for apartment fundamentals for predominantly institutional-grade properties indicate a bottoming of the market in late 2020 and into 2021. On an annual basis, rent growth is positive albeit muted while occupancy rates post slight declines before ticking up in 2022. New supply forecasts range from 300,000 – 400,000 units in 2021 as construction delays because of the pandemic and downturn cause timelines to get pushed into next year. Apartment owners and operators are preparing for a challenging 2021, budgeting for declining revenues and increasing costs, both on the operating side and for capital expenditures.

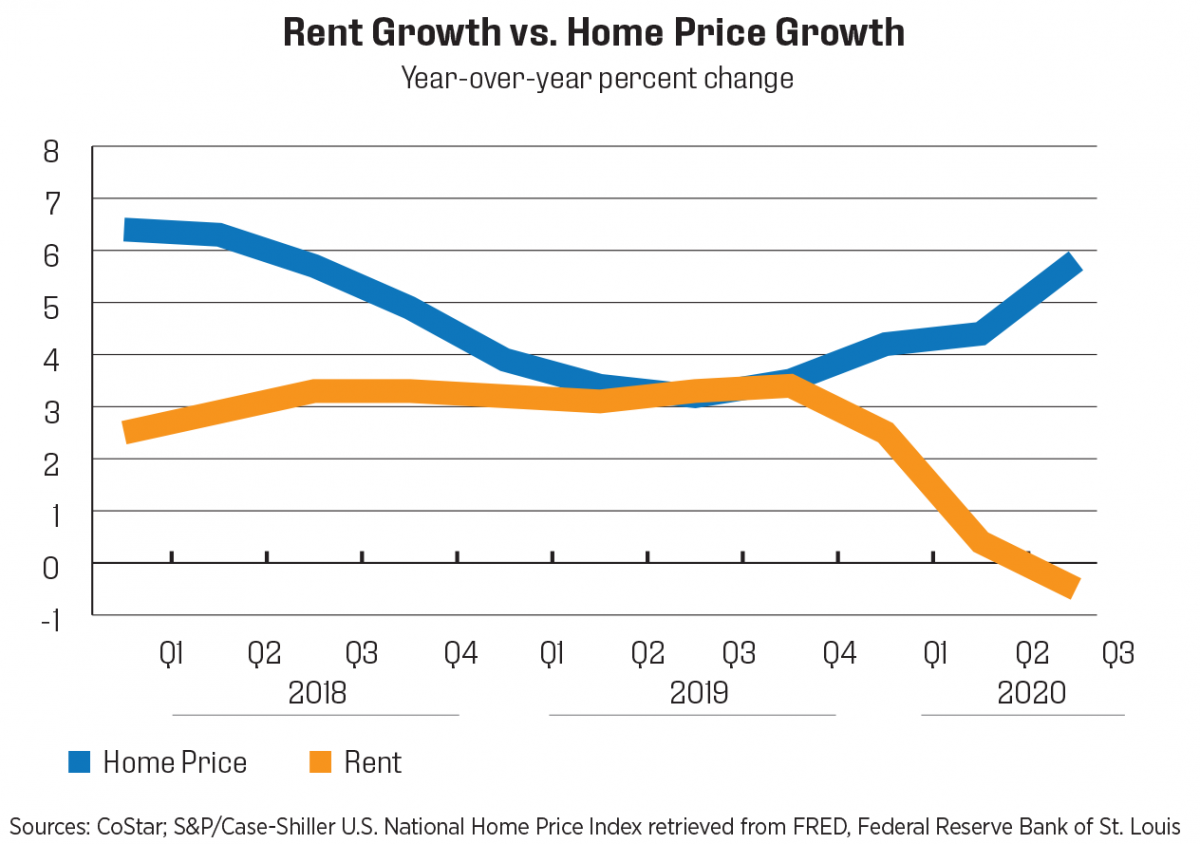

Although overall market fundamentals are expected to be weak in 2021, there are numerous tailwinds for multifamily demand on the other side of the pandemic. The single-family market was far more under-supplied than the multifamily market prior to the pandemic. Increasing costs of materials, particularly lumber, and the feverish pace of demand will put further downward pressures on single-family supply, which are already at historic lows by some measures. The growing gap between home prices and rent growth means renting will be a better option in many areas, although low mortgage rates will continue to be a draw to homeownership. With some 26.6 million 18 to 29-year-olds living with their parents, according to the Pew Research Center, pent-up demand can be expected once this cohort enters the job market and/or attains more solid financial footing.

Finally, friendlier immigration policies from the next administration could be an additional source of demand, as immigrants are a strong renter cohort. According to the Joint Center for Housing Studies, 83% of immigrant households who have been in the country for fewer than 5 years were renters and that figure stayed elevated at 70% for those who immigrated 5-10 years earlier and 57% for those in the country for 10-20 years.

Longer term, the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis could fundamentally change ownership structures for rental housing, further exacerbating affordability issues. According to CoStar, more than one-third of 1- and 2-star properties, sometimes referred to as “naturally occurring affordable housing,” are owned by individuals. Without the advantage of scale and other resources that larger companies benefit from, these owners are more susceptible to financial strain than other market segments and are less likely to be able to contend with increasing delinquencies. In fact, a survey of low- and moderate-income housing providers conducted by the National Leased Housing Association in October found that 89% of owners had already experienced revenue declines averaging 12%. These individuals provide housing for residents who tend to be lower-wage earners, have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and who could see additional financial hardship without more fiscal stimulus. With the gap in rents of 4-5-star properties (newer, more amenity-rich) and 1-2-star properties averaging 57%, losses of this type of stock because of potential foreclosures could be detrimental to affordability in the United States.

Paula Munger is Assistant Vice President, Industry Research & Analysis for NAA.